In a workshop to discuss how academic and creative writing are related, my colleagues and I spent most of our time talking about guilt. All of us felt guilty about the hours we had spent writing novels, stories, and memoirs, which we had been taught to think of as an indulgence.

“I’m not getting paid to do this,” said one colleague, who worried about the ethics of devoting time to her memoir.

“There are people out there robbing banks!” I said finally. “There are a lot of worse things we could be doing.”

Why would a group of university professors feel so guilty about creative writing?

In twenty years of writing novels alongside academic books on literature and science, I’ve encountered the greatest skepticism from fellow scholars. This does not hold true for colleagues in creative writing, who have been encouraging and supportive. To them, it has seemed completely natural that I would write novels--who wouldn’t want to? This uneasiness of professional people toward fiction extends far beyond academia. Tell co-workers that you’re writing a novel, and you’re likely to get nervous glances, as though you were going to describe your dreams. Talking about your novel is received as a breach of taste, as though you were sharing something deeply personal, of little interest to others. (No doubt some colleagues also worry that they will appear in your work.) This July, I’m hoping to graduate from Warren Wilson College’s Low Residency MFA Program in Fiction, and everything I’ve learned there contradicts the view that creative writing is an indulgence. Writing well takes intense work that builds skills relevant to almost any field.

Writing a story requires the ability to see the world from another person’s point of view. This means starting with the senses: what a character sees, hears, feels, smells, and tastes, all of which are likely to reveal her emotions and her unique way of seeing the world. Fiction-writing resembles method acting in that it leads writers to revive their own experiences so that they can imagine the experiences of others. “We represent other people’s minds using simulations of our own minds,” writes psychologist Lawrence W. Barsalou (Barsalou 2008, 623). Barsalou is talking about living, not writing, but the skills built in each realm are relevant to the other. Physician and literary scholar Rita Charon has built the field of Narrative Medicine based on her observation that people skilled in reading, analyzing, and telling stories often make better listeners and better doctors (Charon 2006). A story will only work if the character from whose perspective it is coming can convey her sensations, thoughts, and emotions so vividly, they feel like lived experiences.

Inhabiting the mind and body of a fictional person forces one to think beyond oneself. This is especially true if the person is of a different age, gender, nationality, race, or class--if the character has different ideas or a different body. Some writers believe that one shouldn’t even try to depict characters substantially different from oneself, because one will just propagate stereotypes. I disagree. If the writing involves research (such as talking to people whose lives differ substantially from yours) and an honest, focused attempt to imagine an unfamiliar perspective, what more valuable learning experience can there be? Consider the advice of novelist Robert Boswell on how to write a political novel that is also a work of art: “Write from the point of view of the other” (Boswell 2008, 139). Boswell encourages a writer to tell her story through the eyes of a complex character who sees the issue differently. Good fiction shouldn’t just make readers rethink the ways they see the world; it should do the same for the writer (Boswell 2008, 153). Few learning experiences bring greater benefit than imagining the mental life of someone who disagrees with you.

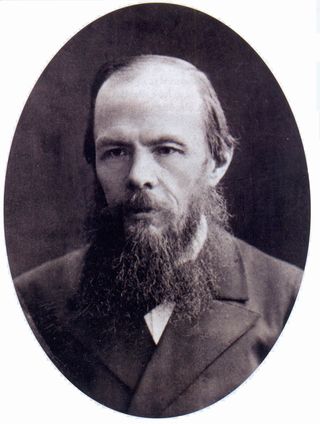

Fiction allows conflicts to emerge that are often suppressed in polite life. Novelist Charles Baxter has observed that “in fiction we want to have characters create scenes that in real life we would typically avoid” (Baxter 2007, 121). Writing a story requires a writer to see the central conflict in an emotional mess and articulate it from several characters’ points of view. What makes Dostoevsky’s writing so great, said my college teacher, Liza Cheresh Allen, is that “no one has a corner on the truth” (Allen 1981). Dostoevsky’s characters often disagree violently, but each makes her case in a sympathetic way so that readers can feel her humanity. In a story worth reading, something has to happen; characters have to confront each other, and they have to act. Action only becomes possible when a writer finds a way to dissolve the forces suppressing a conflict.

Once characters emerge from writers’ minds, they may seem to have independent lives. Novelist David Haynes urges both readers and writers to remember that characters have agendas: often, they are trying to make themselves look as good as possible (Haynes 2016). Readers need to keep in mind what aspects of a story the character telling it may want to distort or conceal. Writers need to consider what a character is avoiding and make the character face what she dreads. Fiction-writer Kirstin Valdez Quade warns writers about slippery protagonists who find ways to avoid confrontations that would make marvelous scenes (Valdez Quade 2016). She urges writers to keep characters in uncomfortable situations so that something surprising or powerful can emerge.

Imagining another person’s internal life; inhabiting the mental world of someone whose views oppose yours; articulating a conflict from multiple viewpoints; considering the agendas of people creating narratives. To what job or field of learning would these skills not be relevant? Writing stories develops these abilities, whether one is writing a science fiction tale or a love story, whether one is studying in an academic program or learning how to write on one’s own. The idea that fiction-writing is personal and self-indulgent comes from the fallacy that writing means withdrawing from life. On the contrary, writing fiction means embracing the world: rethinking one’s experiences, imagining other people’s experiences, and reaching toward what is not yet imaginable. I would urge anyone who has ever wanted to write to get started and ignore any talk of guilt. Some would argue that this will flood the world with bad fiction, but they may also fear the astounding writing that will emerge. Widespread writing could create teachers, doctors, business-owners, and designers who are better observers and better listeners. The failed writer isn’t the one who can’t get published; it’s the one who has always wanted to write but never tried.

References

Allen, Elizabeth Cheresh. 1981. “Images of Women in 19th-Century Russian Literature.” Undergraduate course, Yale University.

Barsalou, Lawrence. 2008. “Grounded Cognition.” Annual Review of Psychology 59: 617-45.

Baxter, Charles. 2007. The Art of Subtext: Beyond Plot. Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press.